Zero and cipher

Cipher/zero, cuneiform, Gilgamesh, and, of course, romance novels

CIPHER, n. These days, when we talk about a “cipher,” we usually mean a code, but it used to be that “cipher” meant a number, any mathematical figure—like French chiffre—and before that, it used to mean specifically “zero.”

The “code” connection here is that lots of encoded text used to be written in numbers (ciphers!) instead of letters.

More fun: “cipher” and “zero” come from the same root. Medieval Europeans got the concept of “zero” from Arabic mathematicians, who were using “صفر sifr,” which means empty/void. (Pausing here to say the initial s of sifr has a dot underneath it on Wiktionary; I can't type that character in Ghost, but if you want to hear how it's different from English s, click the speaker icon next to "pharyngealized voiceless alveolar sibilant." There are a few other special characters missing from this newsletter—apologies—but this one is the most noteworthy.)

Arabic mathematicians, in turn, had borrowed the concept from Indian mathematicians using Sanskrit “शून्य sunya,” which also means empty/void. Arabic sifr enters Medieval Latin in a variety of spellings, including “zephirum/zephyrum” (preferred by Fibonacci, the guy with the sequence) and also “cifra” (sorry we’ve reached the end of my knowledge of medieval mathematicians). In zephirum and cifra, we can see that non-Arabic speakers aren't quite sure what to do with the pharyngealized s of sifr. (I'm not sure how Medieval Latin speakers would've pronounced the first consonant of "cifra," but my guess is tch.)

Zephirum becomes zefiro in Venetian, and then speakers stop bothering with that middle syllable—who has the time!—and we end up with “zero.”

I was really hoping that Arabic sifr was a cognate with the Biblical Hebrew root ספר SFR, which means “to count” (to number, but also to tell or to narrate), and which gives us the Hebrew word “sefer” (book), but my hopes were dashed. They’re not related.

However, my journey to discovering that they’re not related led me to a charmingly twentieth-century website about etymology called Take Our Word for It, which I just have to share with you. Among their claims to fame:

Melanie gets credit for having Yahoo! create an etymology sub-category under their linguistics category and, you guessed it, this site was the first etymological site listed there.

Oh my God, remember the internet before search? I sorta don’t. I feel like I excavated an ancient palace full of clay tablets, ready to be deciphered (more on this below).

Melanie and Mike of Take Our Word for It also wrote about zero, and it’s pretty similar to what I wrote above so I won’t quote, except that they credit Babylonians with the concept, which really keeps us on the topic of ancient Mesopotamia.

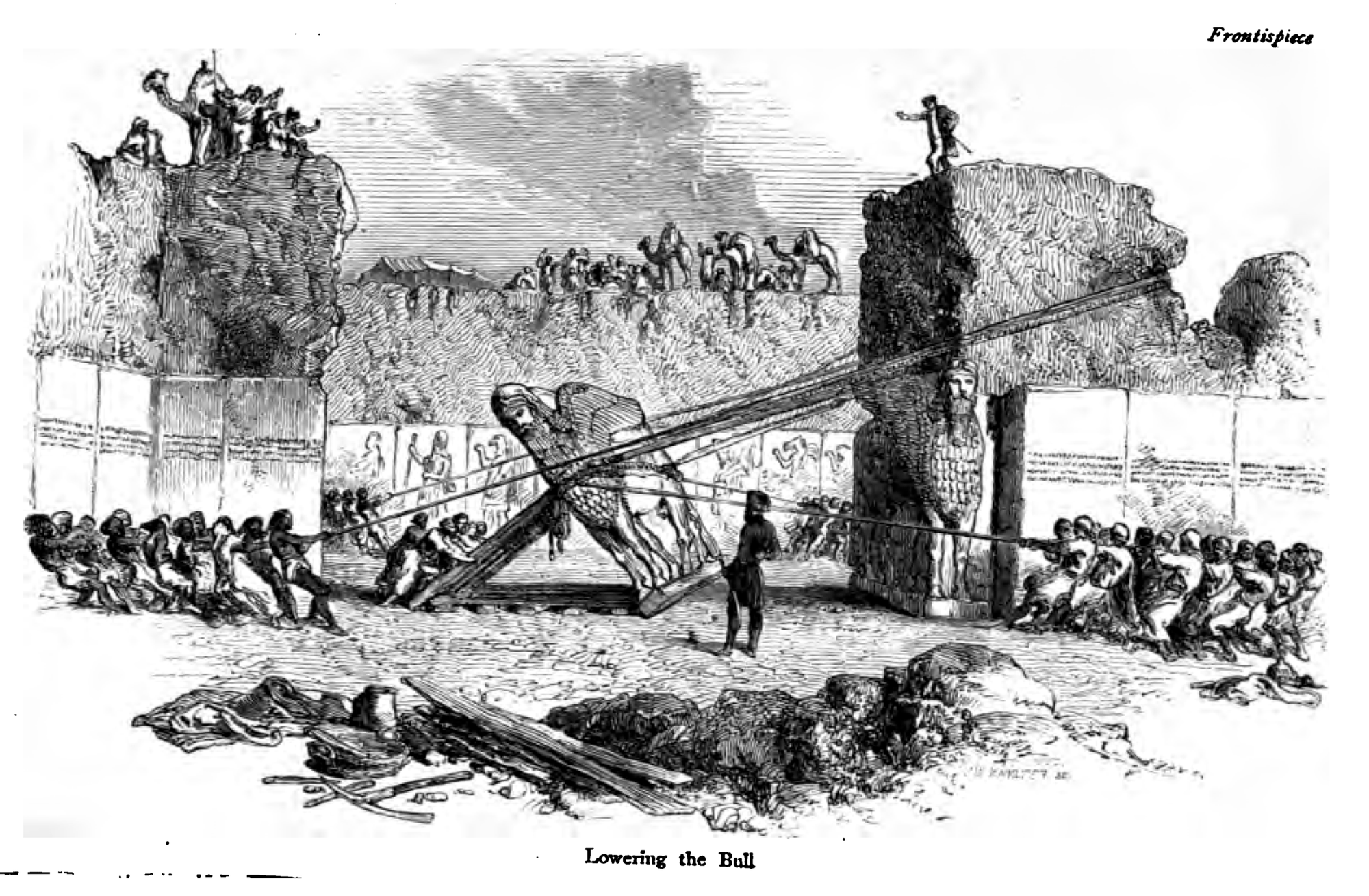

In things that are neither Romance nor romance, I read Joshua Hammer’s The Mesopotamian Riddle, a nonfiction account of how Old Persian and Akkadian cuneiform were deciphered, which was fascinating. It contains a lot of various imperial horrors (British, French, Ottoman, Assyrian, etc.) so unless you are a weirdo who is escaping the 2026 news by reading about bad times in history (hi), caveat lector. I started this as a library audiobook, but my time ran out, so I checked out the print version and I’m very glad I did, since it has all the cuneiform signs in the text, plus illustrations of the ancient sites and photos of the 19th-century scholars.

At one point in this book, Hammer raises the possibility that the Assyrians, who appear in the works of ancient Greek historians and in the Bible as bloodthirsty conquerors, might have been the victims of bad press—history written by their enemies—and that perhaps once their own language was deciphered and they could speak for themselves, our impression would change. And then so many of the inscriptions translate as, like, “here’s how I, king of the Assyrians, starved and flayed the people of this city and murdered all their children.” Yikes. Sure they also had science and art and literature and all that, but I’m pretty stuck on the torture and slaughter.

Meanwhile, a couple millennia later, two brilliant, obsessive men work out how to read their mysterious mix of logograms and syllables. One of them is English and the other is from Northern Ireland, and you’ll never guess who gets all the credit and who gets shamefully mistreated. In theory, I read The Mesopotamian Riddle because I’m germinating a new novel idea that has a main character who deciphers unknown texts, but in practice I read it because it was gripping as hell.

While I was thinking about ancient Mesopotamia, I checked out a library audiobook of Stephen Mitchell’s translation of Gilgamesh, which I’d never read. The Assyrians did not write Gilgamesh, which is Sumerian and predates their empire by centuries, but they did preserve the story in the palace library at Nineveh—the 1850s excavation of this site outside modern-day Mosul is described in The Mesopotamian Riddle and shown in the illustration above—so that’s one good thing they did. Gilgamesh is wonderful. For an epic, it’s bite-sized (it takes about two hours to listen), so if you’ve never read this oldest of stories, I highly recommend it. The passages about friendship and intimacy and grief are genuinely moving, as are the vivid descriptions of the ancient city of Uruk. And it’s sexy and so queer! The poem treats sex as a civilizing, humanizing force, which feels radically different. Also, you know when you’re the biggest, strongest, most beautiful man, and you hear about another big strong beautiful man, and you just have to fight him? You have to crash your heads together like bulls and then afterward, you have to embrace as a man embraces his wife. And then you’re intimate friends for the rest of your lives, which don’t last forever, no matter what kind of quest you go on.

Well, we're not immortal, but we are alive right now, and I am using my limited time on this Earth to read small-r romance:

The Romantic Agenda (allosexual cis m/asexual cis f, contemporary) by Claire Kann. I read this for my library’s Queer Romance Book Club and it’s very cute. Joy is in love with her best friend and boss Malcolm. Their stifling codependent relationship isn’t avowedly romantic, but it keeps preventing Malcolm, who is also asexual, from making lasting romantic connections with other partners, something he really wants. Malcolm was the first out asexual person Joy ever met. Over the years they’ve grown so close that they’ve forgotten how to let other people in. That changes when Malcolm meets Summer. He books a trip to a cabin to woo her, but they each invite a friend to come with them. Summer invites her friend Fox and Malcolm, of course, invites Joy. The four of them manage to have fun despite all the awkwardness of the arrangement, and Fox and Joy particularly hit it off. For the first time in years, Joy begins to envision a life where she isn’t in love with Malcolm. The romance is purely sweet; the main conflict lies between Joy and Malcolm. I thought Joy’s life as a Not-Instagram fashion influencer, especially as a Black woman and an out asexual one, provided really interesting context for her difficult friendship with Summer, who is white and allosexual, but who follows Joy on Not-Instagram, admires her, and has developed a parasocial relationship that impedes their real one at first. Library loan.

The Happy Secret of It All (f/f, both cis and lesbian I think?, historical/fantasy, novella) by Cassidy Percoco. I hesitate to confess this here, but sometimes I don’t read book descriptions. This has a lovely cover and it’s written by Cassidy Percoco, whose social media posts about material culture and history I love (and who once elucidated the word “scroop” for this newsletter!), so I figured that I would like it, which I did, and that it would have beautiful fashion descriptions, which it does. What I did not know, but perhaps would have if I’d read the description, was that this novella, set in a fictional country in a sort of 1920s moment, opens with a young woman at a royal ball. She’s wearing a dress she made herself and she’s keeping out of sight of her step-mother and step-sisters. Oh! A retelling! The prince, a suit-wearing, cane-using disabled lesbian playboy, is a particular delight. This is really deliciously written, vivid in feelings and setting, and I loved it. As any good fairy tale must, it ends with a kiss. Indie published; purchased from Kobo.

That's all for this time. And since we're now in Perfectly Even February, I'll be back in your inbox on February 15.

Word Suitcase is a free newsletter about words and books. If you enjoyed this one, subscribe by email or RSS for the next one. If you know somebody who'd like reading these, please pass it along!

Websites do cost money, so there is a paid subscription option and a tip jar for one-time donations. If you feel moved to support me, I’m very grateful. But please don’t feel obligated. I love having you as a reader either way.