French letters and English hats

condoms, romance novels, rivers of forgetfulness, and loving monsters

CONDOM, n. This word has been on my mind because I’ve read a couple of Judy Cuevas/Judith Ivory’s historical romances and I’m thrilled that she mentions contraceptives. Here’s a passage from Beast (1997), set in 1902, which opens with a scene where the hero, Charles, has just had sex with Pia, his mistress, who is not the heroine of this romance novel. This passage is emphatically unsexy:

Something cold and wet flopped against the inside of his thigh. A sheath, still half on. His capote anglaise, his English hat. With an annoyed tug, he plucked it off. He hated wearing such devices, but Roland [Pia’s husband] was as promiscuous as a tomcat. Charles was afraid of getting some dread disease. Thus he put the bonnet up on his carriage, so to speak, whenever out with Pia for a pleasure ride.

And here is a passage from Black Silk (1991, previously discussed), set in 1858, in which the hero, Graham, has a delightfully bookish and linguistic relationship with contraceptives:

…discreetly wrapped his somewhat controversial purchase into a book-shaped little pack.

In the course of this portion of Graham’s education in bookstores, he learned to ask for “French letters” in England, “English hats” in France. It amused him, even now, thinking of this distinction. Aside from the national slur each country intended, these images also unintentionally revealed each country’s national character. No matter what they called it, the English envisioned the item neatly wrapped up, out of sight; the French envisioned it on, like a jaunty cap. There were other names besides “sheath.” If a gentleman bought these conveniences at a more sordid establishment, he might have to use the dirty name, c——m; even the most salacious literature never wrote the word out. Graham wasn’t certain how to spell it. Condim? Condom? Condum? But he knew how to say it, in several languages, in a dozen euphemisms, up and down the class system, on and off the Continent.

I was aware that condoms were “French letters”—I named a series this, a joke that stuck—but I didn’t know about the censoring of “condom” in 18th- and 19th-century print. One thing I love about Ivory is that her novels feel like they’re in conversation with the literature and ideas of the period she’s writing about. She’s just such an obviously well-read writer.

Graham not knowing how to spell condom due to censorship feels just right for the larger mystery that surrounds this word: nobody knows where it comes from. There are some hypotheses: it’s from the name of the person who invented it (no proof, we don’t know who the inventor was); it’s from the French town Condom (also no proof); it’s from classical Latin quondam, meaning formerly or at one time (no proof, also, why?); it’s from Italian guantone, meaning large glove (sorry, we still don’t know). People were too ashamed to print the word “condom” for a long time, so I suppose it makes sense that its etymology would be extremely difficult to trace.

Beast (m/f, both cis and het historical) didn’t make me feel like I could see into new dimensions in the same way that Black Silk did, but this is, admittedly, a tall order for a small-r romance novel, or any book.

It is fun as hell, though.

I mentioned this book last week because it has some Baudelaire poems translated by Yves DuJauc, an anagram of Judy Cuevas, for whom Judith Ivory is a pen name. “Historical romance novel with the author’s own Baudelaire translations” is so much my catnip that it almost feels like I dreamed it.

Baudelaire’s poem “Le Léthé” is quoted/translated in brief as an epigraph to the whole book and then again at greater length at the beginning of Part 3. In both quotations, the poem’s title is given as “33 of Les Fleurs du Mal.” The other two Baudelaire poems in Beast are also numbered. Since Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) has had many editions, variously censored and not, some with additional initially unpublished material, I don’t find these numbers a useful way to identify the poems. This is a long way of saying that Ivory doesn’t translate the title “Le Léthé,” so here’s me telling you that in English this poem is called Lethe, after the river of forgetfulness in the underworld in Greek myth.

What’s it about? Well, the poet’s in love with a beautiful woman who doesn’t love him back. A classic. Play the hits, Charlie B. She’s a “monstre,” but he’s wild about her. It’s a desperate, darkly erotic poem, as the poet begs to sleep with the heartless monster woman so he can forget himself (and… die?) in sexual ecstasy in her bed. If you haven’t read any Baudelaire and you’re wondering either “how sexual can this poem from 1857 be?” or, on the other end of the spectrum, “is the river of forgetfulness her vagina?”, shift your impression toward the latter. There are verses about plunging his fingers into her hair/mane and burying his head in her petticoats to smell the sweet odor of his dead love. But the poet also yearns to suckle nepenthe (mythical drug for forgetting) and hemlock from her breasts, so it’s not only vaginal. So that’s (some of) what’s up in this poem. Also, it’s fantastically beautiful. I love Baudelaire. Here’s the full text in French with a selection of public-domain English translations.

Now that we know a little more about this poem, let’s see what it’s doing in a romance novel. Beast, which is, of course, a riff on Beauty and the…, opens with this epigraph:

Come, my languid, sullen beast,

Come lie upon my heart…

Charles Baudelaire

33 of Les Fleurs du Mal

DuJauc translation

Pease Press, London, 1889

Please note that, just as Yves DuJauc is an anagram of Judy Cuevas, “Pease Press” is the fictional publishing house where the heroine of Black Silk sends chapters of her serial novel. “London” and “1889” are equally fictional details. I am already having a great time.

What’s being translated here? Sort of the first two lines of “Le Léthé,” which are

Viens sur mon cœur, âme cruelle et sourde,

Tigre adoré, monstre aux airs indolents;

Even in two lines, there are a lot of interesting choices. (“When Americans say ‘interesting,’” one of my French professors used to say, “they mean ‘I don’t like it.’” A blistering and accurate critique of my people, but I promise in this case I do actually mean interesting. I am interested! I want to talk about it!)

“Viens sur mon cœur” as “come lie upon my heart” is lovely—and straightforward.

The remainder of the passage is beautifully loose. The rhyme scheme and the syllabic meter of the French are traded for free verse in the English. I like that. Not that the formal qualities of the poem aren’t important, but the great thing here is that Judy Cuevas is doing her own translation for her book, so she can direct the spotlight where she wants it. She’s shining it on the invitation (“come”)—which she repeats, unlike Baudelaire—and on this idea of being in love with a monster.

But she doesn’t use the word “monster.” She says “beast.” This is combining two ideas in the original, I think, “monstre” and “tigre,” and more than that, she’s pointing that spotlight right at Beauty and the Beast. Because it’s a sexy monster, genre romance’s favorite kind. I mean, what other kind of monster would you invite to lie upon your heart?

Even in two lines, things get intimate: the repetition of “come,” and then “aux airs indolents” becomes “languid,” like we’re already lying in bed.

In Cuevas’s translation, “sourde” (deaf/hard of hearing, but also dull/muffled) becomes “sullen,” which is an unusual, evocative choice. I think Baudelaire’s beloved is “sourde” because she’s willfully not listening to the poet’s misery, since “sourde” is paired with “cruelle.” But the omission of “cruel” changes the mood radically, so the “languid, sullen beast”—the listless/weak, dull/gloomy creature—is almost an object of pity. But still one that you want to lie upon your heart.

It’s also worth noting that Baudelaire’s monster, in the full text of the poem, is inarguably female—though often described with masculine nouns like “tigre” and “monstre.” In Cuevas’s longer translation from this same poem, the one that appears later in the book, it’s clear the poet is addressing and describing a woman. But here in this brief epigraph, the “beast” is not necessarily female, and the lines could describe either of the novel’s main characters. “Come lie upon my heart” could be an invitation from either of them.

What I love most about this translation is that it’s from the novelist herself and there’s such a pleasing unity there: it sounds like something she wrote because it is. And of course I also love that the epigraph to this romance novel is drawn from a pathetically desperate, fatally horny poem about fucking a heartless monster who doesn’t love you back. Hell of a way to start things off, Judith Ivory.

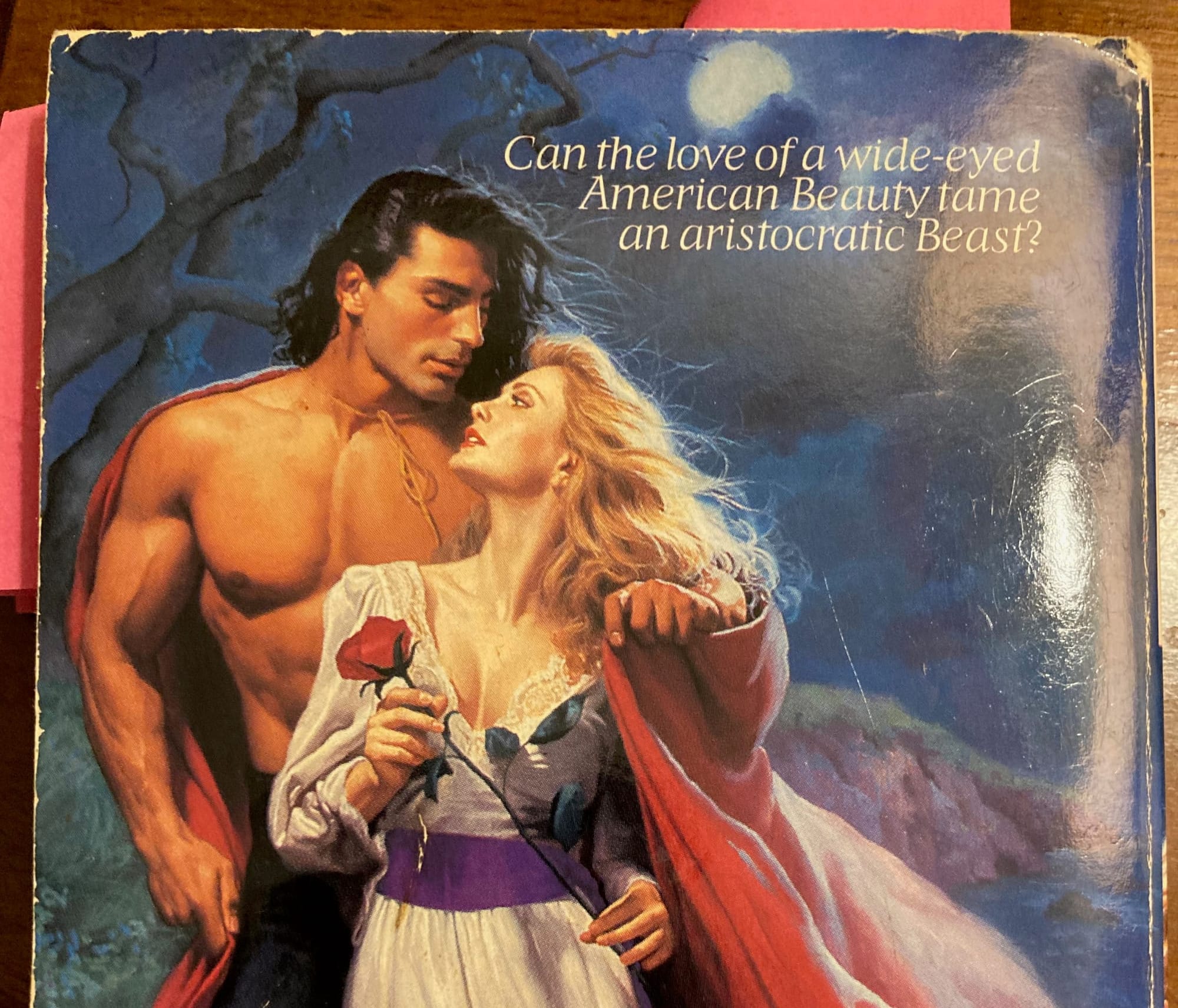

So what kind of book is Beast? As discussed, it’s playing with a few elements from Beauty and the Beast. This one is set on an ocean liner going to France in 1902. He’s a disfigured and disabled perfumer, she’s a stunningly beautiful math-genius debutante, both of them have attitude problems, they’re engaged to be married but have never met. He seduces her on board without telling her who he is or letting her see his face. Bananas! And of course it’s written in Judith Ivory’s prose, so I would want to be there no matter what they were doing. But it helps that it’s outrageous. Two freaks? Check. Do they fuck it up bigtime? Oh yeah.

The amount of sensory description in this is to die for—the perfume, obviously, especially all the chapter epigraphs and in-text reflections about ambergris, which is a substance excreted by whales that, when aged, becomes a precious perfume ingredient. A transformation, you say? Excrement into perfume? Something almost… monstrous that then becomes lovable? Is that some sort of metaphor?

(I know at least two of you want this information: yes, some of the epigraphs are from Moby-Dick.)

It’s not just the ambergris, or the jasmine, or any scent. It’s also the ship rocking in the stormy weather that leaves everyone but our two protagonists seasick, Louise’s black pearl necklace against her skin, the way it breaks, the one loose pearl rolling across the floor of the darkened cabin as the ship tips from side to side… every detail is selected with such care. And then the ship arrives and they enter a new stage of their relationship in the sunny lavender fields of Provence.

Would I like Judith Ivory to lovingly describe Provence to me in superb prose? Yes indeed I would.

And it's not just the sensory description, either. I also love the boldness of the narrative voice. Ivory doesn't feel constrained by deep third-person point of view, or by anything so small as linear time:

Charles reached for her, finding the curving crown of her head, the back of her cool, silky hair, knowing, as he slid into the sexual, he was making a mess of his equilibrium somewhere. He felt upside down, frowning, smiling, drawn hopelessly... He found Louise Vandermeer dear, surprising, puzzling; bright, funny, sweet. His wild, misunderstood thing—he would gnash his teeth at this assessment in only ten minutes (and wish to shoot himself for it in a month's time), but at this particular moment as he leaned forward through the dark to find her mouth, he thought the description not just apt but positively inspiring.

Yes! Bring this back! Step outside the confines of that character's skull. Time travel a little. Give an ominous warning. Pass some judgments. Is it easier to write a character who's being a damn fool if you're willing to let your narrator say "look at this guy, being a damn fool"? I don't know, but my study will require me to read a hundred more romance novels that aren't scared to play with narration, and I bet I'm not going to find many that were published in this century.

Beast has a few features that made me grimace, like a big age gap (Louise is 18, Charles is... 38?) and some pretty wild Orientalism, but I think the book is using both of those things, poking at them and turning them inside out, and, of course, depiction is not endorsement and a romance novel is not an instruction manual. It would be loser behavior for me to proclaim that what I want in a romance novel is to see two freaks fuck it up bigtime and then start to fidget when the freaks do fucked-up shit. But sometimes I am a loser!

Charles lying to his fiancée about his identity so he can secretly seduce her while they both take the same ocean liner: ohohoho, yes. Charles pretending to be an Arab as part of his disguise: yikes. Both of these things are bad to do in real life! But one feels like classic romance novel shenanigans, and you know he’s gonna pay for his terrible choice, and the other feels genuinely uncomfortable. Your mileage may vary on how much you’re willing to dwell in the bad feelings here. I would absolutely understand anyone who simply said “no thanks” upon hearing this.

While sorting out my own bad feelings about Charles, and to a lesser extent Louise, I really appreciated Alexis Hall’s 2015 thoughts on Beast:

I think Charles and Louise are both fascinating, actually. I thought the character work through the whole novel was … amazingly deft, especially because Ivory doesn’t flinch from making them both deeply unpleasant in a lot of (very human and understandable ways). What really struck me about the fairytale aspects of the story was that, really, they’re both Beauty and they’re both the Beast, fantastical outsiders in what is otherwise quite an everyday world.

I did really almost quit this book—a historical romance in superb prose, with Baudelaire translations, basically made for me!—because both Charles and Louise are deeply unpleasant at times, and I didn’t want to hang out with them. But by the end, their story was compelling enough that I didn’t want to be anywhere else. It has its flaws, but I loved it. Come, my languid, sullen beast, come lie upon my heart.

This is the warning that my past self would have wanted: those condoms that this book and I made such a big deal of up above? Yeah, they fail. There’s an unplanned pregnancy in this book.

Lastly, it’s my honor and my pleasure to let you all know Sherry Thomas also wrote about this book in 2002: “Beast by Judith Ivory is one of my two all-time favorite romance books and also simply one of the best books I have ever read.”

As soon as I started reading Beast, I thought about the masked shipboard seduction in Thomas’s Beguiling the Beauty (previously) and the way that the two main characters of Delicious (previously) only meet in the dark for a huge portion of the book. Obviously Beast had a huge influence on Thomas’s work. Finding these connections delights me.

I will be back in your inbox on October 26 with some seasonally appropriate romances.

Word Suitcase is a free newsletter about words and books. If you enjoyed this one, subscribe by email or RSS for the next one. If you know somebody who'd like reading this, please pass it along!

Websites do cost money, so there is a paid subscription option and a tip jar for one-time donations. If you feel moved to support me, I’m very grateful. But please don’t feel obligated. I love having you as a reader either way.