Ticklishly pleasing

Judy Cuevas, tiles, and my new theory of romance novels

IMBRICATE, adj., v. I first encountered this word in Judy Cuevas (later Judith Ivory)’s historical romance Black Silk (1991). The hero, Graham Wessit, is studying the heroine, Submit Channing-Downes, during their first meeting:

The shy, imbricate smile—no more than a social mechanism, but ticklishly pleasing, as if it ran lightly over his skin. Then gone.

Not knowing the meaning of “imbricate,” I guessed that it had something to do with bricks, and wondered if maybe Submit’s smile was like a brick wall—unreadable. On that count, I was wrong.

“Imbricate” originally meant the overlapping of roof tiles, and then came to mean the overlapping of animal scales. Etymologically, it’s not especially interesting: it comes directly from Latin “imbricatus,” meaning the same thing. As a verb, it means to place in an overlapping pattern like tiles. “Imbricate” is not related to “brick,” which comes to both English and French (brique) from Middle Dutch and is related to the word “break.”

So while there is an architectural connection, Graham thinking of Submit’s smile as “imbricate” refers to the slight overlap of her crooked front teeth, an unconventional feature that transfixes him. This obsession transmutes into admiration. As he slowly falls in love with Submit, he even dreams of running his tongue over her teeth while kissing her.

“Imbricate,” an unusual, intellectual word, is the perfect description for Black Silk, which is itself kind of a tiled pattern of Graham and Submit—“two stupid, messy humans”—living their lives, occasionally overlapping, and eventually building something that interlocks. In structure, it’s very different from a typical romance. Graham and Submit don’t meet each other for quite a long time, and even after they do, Graham remains involved with another woman, Rosalyn, for a good three-quarters of the book. He has sex with Rosalyn on page, something I think used to be more common in historical romance but that has all but vanished from more recently published work. Showing Graham’s sex life is emblematic of the kind of risk this book is willing to take; many readers will find this distasteful or unforgivable, and indeed, in the GoodReads reviews for this book, you can see that a lot of readers were put off by Graham’s genuine flaws or the book’s unusual structure or slow, careful pace.

In most historical romance I’ve read—a corpus heavily weighted toward recent publication—there’s a desire for the hero to be “a rake” in a sort of airbrushed, sanitized way. He only sleeps with widows and opera singers! He’s very discreet! He has a reputation that we can titter about, but that won’t really hurt anyone! Not so in Black Silk. Graham suffers. He’s dragged to court for a false paternity suit and is unable to proclaim his innocence because of his disastrous reputation; everyone believes he would abandon a lower-class girl to give birth to his children alone. He’s slept with a servant in the past, after all.

Sleeping with a servant would normally be such a shocking and awful thing for an aristocratic hero to do—1850s supporting characters and modern readers alike will wring their hands about the unequal power dynamic—but in Judy Cuevas’s hands, the particulars of this past relationship and Graham’s treasured memories of it are actually one of the sweetest parts of the book. Margaret, the woman in question, is fleshed out in a way that makes clear that this was her choice, and she didn’t suffer for it, and she’s wonderfully real and memorable.

So is everyone in this book. There’s Graham, of course, with his absurd passion for wearing five pocket watches and many rings at once, his physicality, his love of the chemistry of fireworks and photography (he's literally and figuratively "flashy," dear Judy Cuevas I love you), who’s paired brilliantly with Submit, reserved and intellectual and so devoted to her late husband that she dresses in severe black for a long time after his death.

Her late husband, Henry, is another of this book’s fascinating characters—an angel in Submit’s eyes and a devil in Graham’s. Henry was Graham’s guardian after Graham became an orphan. Graham’s wild ways disappointed him gravely, and once Graham grew to adulthood, they lost contact. Yet Henry brings Graham and Submit together by including a provision in his will that Submit should deliver a certain box to Graham after Henry’s passing.

The box, black lacquer with orchids on its lid, is lined in black silk—a very different usage of the titular fabric from Submit’s mourning dress—and full of erotic illustrations of Graham and a former lover. These, a youthful folly of Graham’s, got him expelled from school and in serious legal trouble years ago. Henry saved them—and left them for his widow to deliver to Graham—for a complex set of reasons that the book allows to remain ambiguous. It’s revenge porn, it’s a taunt, but it’s also, given some of the other facts we learn about Henry along the way, his own obsession with Graham, a kind of jealousy or possibly even admiration? Regardless, how strange to ask that your widow make this delivery to your rakish ward. Did Henry want Submit to meet Graham?

Allowing things to remain ambiguous was one of the qualities of Black Silk that most amazed me. I can just feel how many decades before GoodReads reviews and the wider internet this book was published; Cuevas is remarkably unconcerned about reassuring readers that she knows what’s right and moral and pure. Graham and Submit meet in a bizarre and uncomfortable circumstance and continue to be bound up in further bizarre and uncomfortable circumstances. These people are messy. They mess up. They also gradually change and try to atone, but it’s handled with remarkable subtlety and a huge amount of… faith in the reader, I think? Judy Cuevas is going to use the word “imbricate” and she thinks you can keep up. She’s also going to demonstrate that these two characters are in love and will make each other happy, even though they have gravely wronged each other in the past, and she’s not going to lay it out in bullet points. She thinks you can keep up with that, too.

I’ve hardly talked about Submit so far, and that just isn’t right. I loved her. Literally and figuratively buttoned up, she’s a judgmental little bitch (yesss), and it drives her nuts that Graham is so lovable, especially since she is not immune. She wants to be immune so bad. Submit is razor-sharp and highly educated and—lest you think from my preceding paragraphs that the wrong lies solely with Graham—she uses her writerly talents to betray Graham profoundly. It rules. I don’t wanna read a love story about two nice people having a reasonable conversation and deciding to start a relationship. I wanna see two freaks fuck it up bigtime!

Admittedly, “Two Freaks Fuck It Up Bigtime” (this is actually one of the entries in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index, I’m pretty sure) is a bigger risk, as a structure, than “two basically normal people have a few mishaps on their way to a romantic happily ever after.” Judy Cuevas is pulling it off because she is a hell of a writer, fearless and lavish, and she is writing her book, not the book that will please you. (Though it does, in my case.)

Black Silk is marvelously specific in both its prose and its characters, and you also see that specificity in Cuevas’s attention to historical detail. She is obviously well read and the book is well researched. Some of her chapter epigraphs come from real nineteenth-century publications—ads that ran in serialized Dickens novels, or quotes from work in Mrs Stephens’ New Monthly—and it gives depth and richness to the storyline about the serial novel inspired by Graham’s life. Other chapter epigraphs are drawn from the correspondence or publications of the novel’s characters, so there’s a mix of fictional and historical.

The serial novel about Graham, The Rake of Ronmoor, is published under the nom de plume Yves DuJauc, which I was assumed was an invention. I questioned this assumption when I read a second novel by Cuevas/Ivory, Beast—more on this one in a future newsletter—where some chapter epigraphs are Baudelaire poems in translation, and the translations are attributed to… Yves DuJauc.

“Wait,” I thought, “is he a real person after all? How come I’ve never heard of this serial novel author who also translated Baudelaire into English?”

Yves DuJauc brings up nothing on Wikipedia or the Internet Archive. In fact, my fifth or sixth DuckDuckGo and Google search result was Beast itself.

So I went back to my first assumption: she made him up. “DuJauc” is kind of strange as a French surname anyway.

And then I thought about “imbricate”—tiles, patterns. And then I thought about

J U D Y C U E V A S

Y V E S D U J A U C

It’s an anagram! Talk about ticklishly pleasing. Shortly after my giddiness subsided, I recalled that Judy Cuevas was a math professor before she was a romance author.

The pen name for the author of fake-novel-within-a-novel The Rake of Ronmoor is her name, scrambled. This is such a delightful little inside joke. Even more exciting, those are her Baudelaire translations in Beast. So she’s a former math professor who can write a novel in English and translate French poetry. Smart cookie.

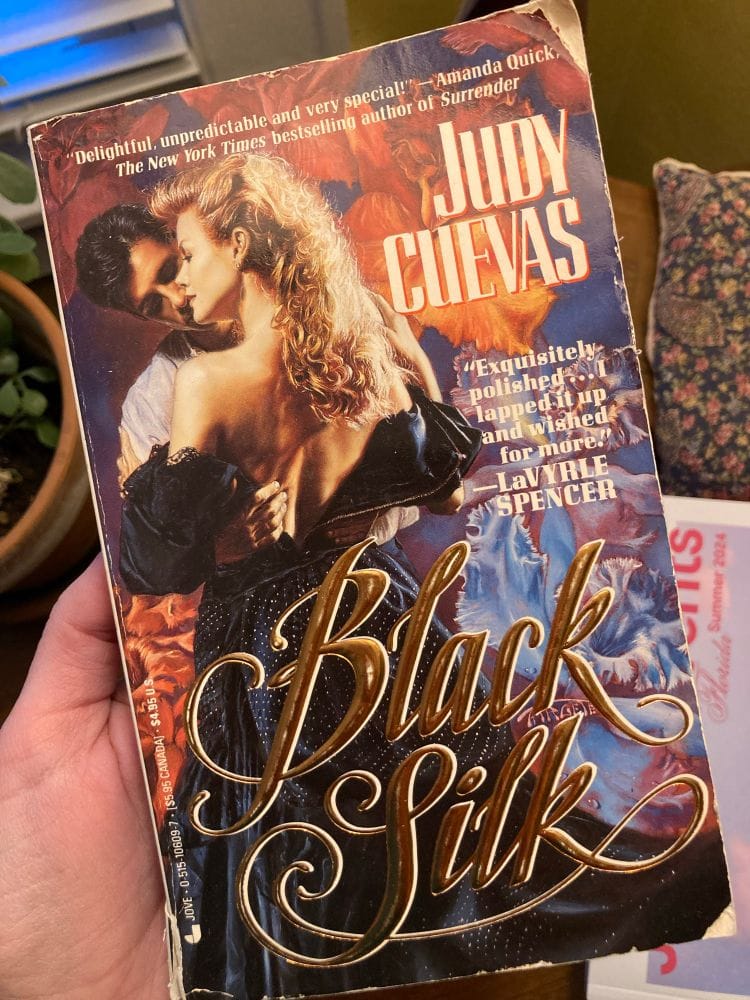

I absolutely love that Black Silk, which I own as a used mass market paperback with an amazingly 1991, horny clinch cover, which retailed for $4.95 USD, is full of Shakespeare quotes, genuine nineteenth-century magazine ads, discussions of Darwin, profoundly eccentric and flawed individuals, inextricably strange circumstances, big messy emotions, and one secret, clever anagram. This book is horny, it is commercial, and it is complicated, and that combination isn’t for everyone, but wow is it ever for me.

You know who else it was for? Beloved historical romance author Sherry Thomas! One of the pleasure of reading a classic of the genre is that sometimes your favorite authors have commented on it, and here’s what she had to say in this 2002 review:

Judy Cuevas is a master of sensual description. Her writing has flavor, succulence and substance. It has that indescribable something that can only be called literary "fat", a quality that makes her particular confection of words deliciously tangible.

This praise for Cuevas’s prose might not seem germane to the Two Freaks theory of romance [1] that I’m germinating, but I think it’s the root of everything. You can’t get me to buy in and cheer for the freaks if I’m not having a good time reading about the texture of the silk and Submit’s crooked teeth. I’m not hanging around for the languorous pacing of this novel if I’m not absolutely captivated by every sentence, every scene. The best, most compelling premise in the world will do nothing for me if the author’s clunking one word after another. Show me Two Freaks in boring, awkward prose and I’m out. A book is made of words. As a reader, I want to marvel at the care with which they are tiled together—imbricated, we might say—in every phrase.

And in this one case, thanks to Judy Cueves/Yves DuJauc, in every letter.

Listen, I’ve written romances with three protagonists, so let me be the first to acknowledge that the name of my theory isn’t quite right yet. The Two Or More Freaks Theory just doesn’t have the same ring. I’m working on it. ↩︎

A few last notes:

I read Black Silk because of Sara's thread of excerpts from it, so this whole newsletter is thanks to them. If you want to know more about this book, you should click that link, and if you've already read this book, you should click that link. Please enjoy this excerpt in particular.

And I just want you all to know that Louis Cole’s song “F It Up” was stuck in my head the entire time I was writing this.

Changing topics, but still on the subject of mess and perhaps relevant to your readerly interests, here’s Garth Greenwell writing about a sex scene in Miranda July’s All Fours and what we might gain from dwelling in bad feelings.

I'm gonna be part of an online panel of queer authors talking about community, audience, and publishing on Thursday, September 18 at 6:30PM EDT. I'll be chatting with Fin Leary, Karmen Lee, TJ Alexander, and Anna Burke, and I think it's gonna be a great conversation, so please join us if you're free!

I'll be back in your inbox on September 28.

Word Suitcase is a free newsletter about words and books. If you enjoyed this one, subscribe by email or RSS for the next one. If you know somebody who'd like reading this, please pass it along!

Websites do cost money, so there is a paid subscription option and a tip jar for one-time donations. If you feel moved to support me, I’m very grateful. But please don’t feel obligated. I love having you as a reader either way.