Pudding eater blues

yeah we're talking about Sherry Thomas again

PUDDING, n. Earlier this month I ate some really good chocolate budino—what Americans would call pudding and Brits would call custard—at a local Italian restaurant. It made me wonder what the hell happened in language that so many of us are using words that originally referred to sausage—“pudding” comes from French “boudin,” blood sausage—to refer to custards, or, in British English, a far vaster category of foods:

[a] boiled, steamed, or baked dish made with various sweet or (sometimes) savoury ingredients, added to a mixture typically including milk, eggs, and flour (or other fatty or starchy ingredients such as suet, rice, semolina, etc.), or enclosed within a crust made from such a mixture.

That’s the OED’s second definition of “pudding.” Number one is a kind of sausage.

The connection between “minced-meat mixture boiled inside of an animal stomach or other entrails” and the far more appetizing sweet possibilities appears to be the notion “boiling/steaming inside of a thing,” per this note in the OED:

The earliest use (connecting this sense with sense I.1) apparently implied the boiling of the mixture in a bag or cloth (a pudding-bag or pudding-cloth), as is still sometimes done; but the term has been extended to similar preparations otherwise boiled or steamed, and finally to things baked, so that its meaning and application are now much more varied. In modern use pudding refers almost exclusively to sweet dishes, with the exception of certain named savoury dishes such as those at sense II.4b.

People go wild with metaphors, man. “This cloth that you boil food in is just like an animal stomach” sure, okay, I guess that’s similar enough, but the leap to “anything boiled or steamed inside of another thing is now ‘pudding’” is a lot to take.

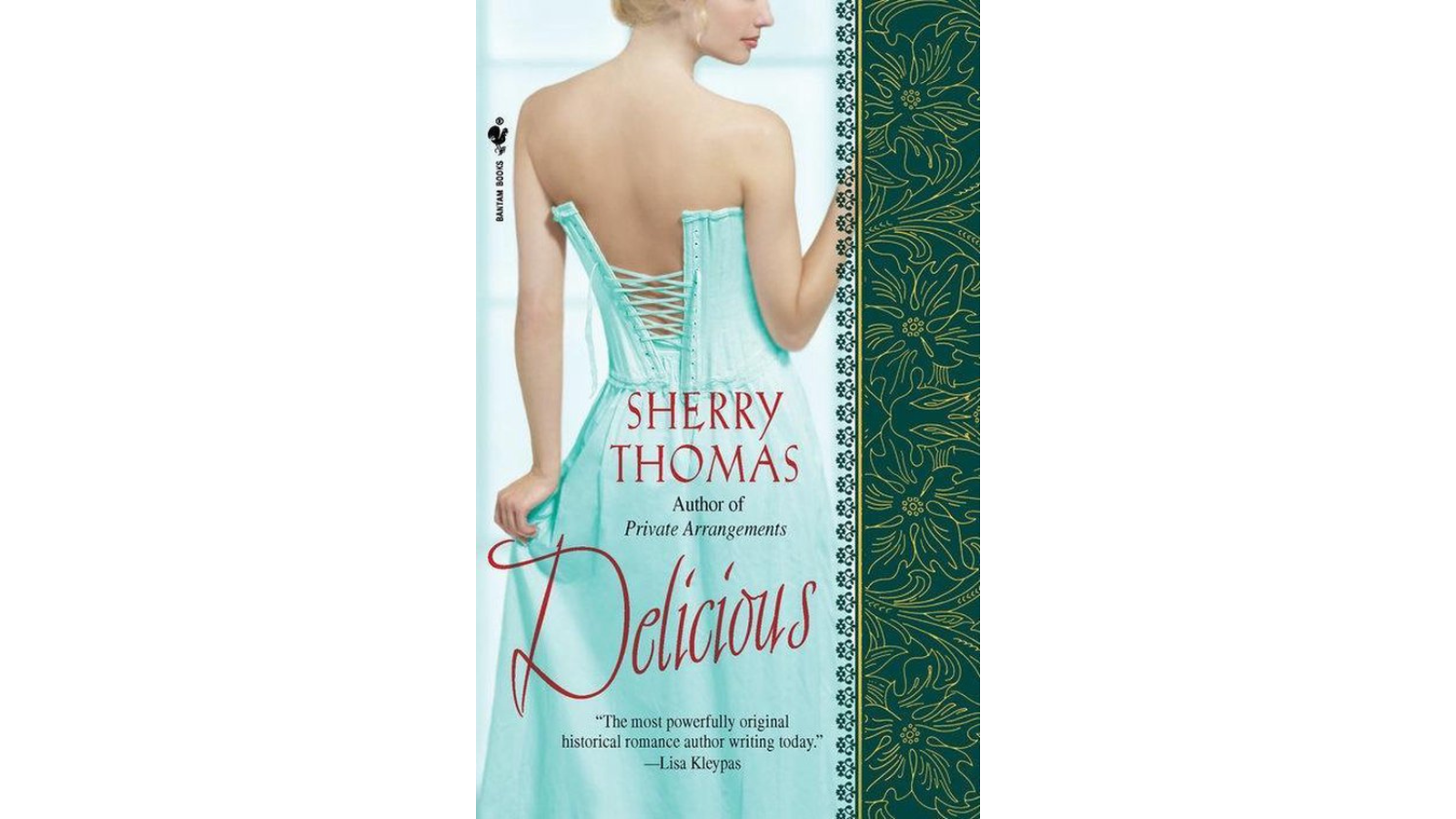

I bring all this up because I wanted to tell you all about Sherry Thomas’s 2008 historical romance novel Delicious (m/f, both cis and het), a riff on Cinderella in which the heroine has been cast out of her aristocratic family for a teen pregnancy and ends up working as a cook.

The novel prominently features chocolate custard. Pudding, for some of us.

In this scene, the hero, Stuart, has just inherited his deceased brother’s house, including the cook (our heroine, Verity Durant). Stuart had a strained relationship with his luxury-loving brother. He himself lives an abstemious life. He does not want his brother’s cook, famous for her skill in the kitchen and infamous for her affair with his brother, or the elaborate multi-course meal she has planned. He wants to eat a sandwich in his office while he works. This causes consternation in the household. They reach an uncomfortable compromise, in which Stuart eats a few bites of the meal but refuses dessert.

But later that evening:

Shortly after his nonencounter with Madame Durant, he’d discovered, set aside in a special holding cabinet in the warming kitchen, a silver dome-covered dish. Under the silver dome had been a small ramekin. He’d known instantly what it was, the dessert course that he had not allowed Prior to serve, despite—or was it because of—the latter’s distressed protests that the chocolate custard was unique, sensational, and intolerably wonderful.

He’d had enough wherewithal then to cover the dish again and close the door of the holding cabinet. But now the chocolate custard was with him, alone, deep in the privacy of the master’s apartment.

He didn’t even have the excuse of hunger anymore. The bread and butter had been wholesome and filling. But he hadn’t been able to stop thinking about the custard, its dark allure, its heady aroma that had made him want to stick his tongue inside then and there.

“Its heady aroma that had made him want to stick his tongue inside then and there.” Is it perhaps possible we are not talking about custard anymore?

Right so “stick his tongue inside” is amazing, 100% super normal way to eat custard, life is too short to use spoons, no further questions.

But what I really, really love in this excerpt is the “But now the chocolate custard was with him, alone,” line. What a marvelously weird way to say it! In mundane language, we’d expect something more like “but now he was alone with the chocolate custard,” and even then, “alone with” still carries, well, a heady aroma, let’s say. It sounds like he’s with a person. But the reversal of the word order—“the chocolate custard was with him”—makes the custard the subject and Stuart the object. The custard is the agent. Grammatically and figuratively, it’s doing something to him.

And then we arrive at that wonderfully offset, emphatic “alone.” What Stuart wants to do to this custard cannot and will not be witnessed by another living soul. And he and his sexy custard are not merely alone and in private, no, they are “deep in the privacy of the master’s apartment.” (Emphasis mine, but like, not really.) I wonder what other sorts of things go on there, in the master’s apartment? Not near the entrance, either. We’re talking about the sorts of things that might happen once a man has fully penetrated the space, deep in its privacy.

Well. He eats the custard, obviously.

Because I can’t resist, here are two more excerpts from this novel. In addition to riffing on Cinderella, it has a Cupid-and-Psyche thing happening: the heroine refuses to let the hero see her face—they spent a night of passion together a decade ago and she’s afraid of what will happen if he recognizes her—so they’re always meeting in the dark or in the pea-soup London fog. This is excellent for other kinds of sensory description, like sound:

Her dress soughed, woolen skirt on flannel petticoats.

“Sough,” meaning to make a rustling or rushing sound, goes all the way back to Old English. Isn’t it lovely? (If you’ve never encountered this word before and aren’t sure how to pronounce it, the OED contains no fewer than five options on that count, so you basically can’t go wrong. That final gh can be [f] or [x] or nothing at all. The vowel can be like “sow,” or the first vowel in “suffrage,” or even like “soup.” English is truly whatever we want it to be.)

And here’s a description of touch and smell:

Her skin was not flawless softness, but that was on par with saying that Helen of Troy did not excel at embroidery. It simply did not matter. It was her; her jaw, her cheek, her eyelashes fluttering against the corner of his lips, her hair and clothes and skin that retained the lingering scent of madeleines.

This is one of my favorite things to encounter in a romance novel: attraction not because the beloved is perfect, but because the beloved’s imperfections are also beloved. Chef’s kiss.

That's all for this time. I have limited childcare in August, so I’ll be back in your inbox on August 31.