Hot organic fusion

digging into a scene from Dance by Judy Cuevas

DELIQUESCE, v. This is the English language’s most beautiful verb for decomposition. It means, essentially, “to become liquid.” Specifically, in chemistry, substances deliquesce when they absorb moisture from the air and melt or dissolve. In biology, organisms or parts of organisms liquefy or melt, either because they’re rotting or because they’re growing into some new form. All that gives rise to a figurative usage: to dissolve, to melt away, to disappear.

I’ve always liked this word, though until recently I was pronouncing it wrong. It’s del-ih-kwess, not del-ih-kess. It’s pretty.

Still, it’s not the sort of word I expect to find in a sex scene.

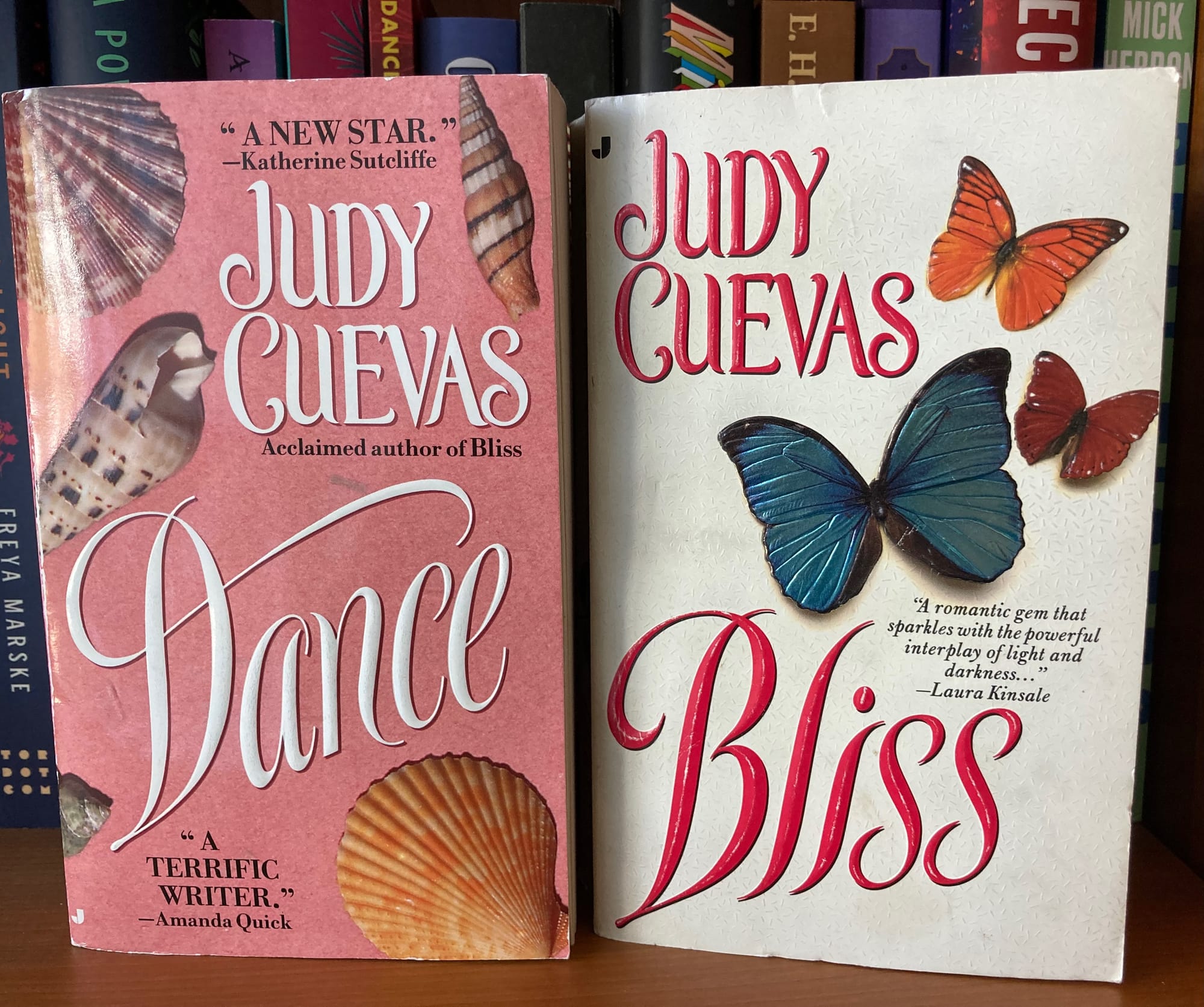

I recently read a pair of Judy Cuevas romances, Bliss and Dance, both out of print and selling for around $100 USD on used book sites—if you can find them at all. Author and extraordinarily generous human being Megan Frampton lent me her copies, for which I am very grateful.

While I was reading each of these, periodically I marveled to myself, “I think this book might be worth a hundred dollars.” I am somewhat embarrassed to say I did buy my own copies after I returned Megan’s. Hey, life is short, the world is terrible, I’m lucky enough that my bills are paid, and sometimes to remember what joy feels like I gotta buy myself an astronomically priced thirty-year-old mass market paperback or two.

I debated whether I should write about two novels that are almost impossible to find. Usually the purpose of this newsletter is to tell you about books that you can read. (Don’t take my word for it! etc.) But for this particular one, the purpose is different: if anybody who knows Judy Cuevas, or anybody who knows anybody who might know Judy Cuevas, or anybody with any connections in publishing is reading this newsletter, please, somebody republish these novels. Make ebooks. There is a market. I will make a market. Get the rights and I will format the ebook myself.

Bliss (1995) and Dance (1996) are set at the turn of the 20th century in France and they tell the stories of the De Saint Vallier brothers, Bernard (“Nardi”) and Sébastien. Descended from a formerly aristocratic family, they’ve lost their ancestral home, the Château d’Aubrignon, which is now owned by a wealthy businessman named Du Gard. The brothers are doing just fine financially, since Sébastien is a bigtime lawyer and Nardi was a celebrated sculptor—until he became an ether addict. Bliss begins with Nardi declaring that he’s made a deal with the Du Gard family to get Aubrignon back: he’s going to marry their daughter Marie. The family has, of course, demanded that he get sober before he enters into the marriage. Restoring Aubrignon is Sébastien’s dream, and Sébastien is the orderly, get-things-done one, so he’s stunned that his ne’er-do-well brother has arranged all this—but of course nothing goes to plan.

While Nardi is living in a cottage on the Aubrignon grounds, under guard to prevent him from buying more ether, Sébastien is at the château, meeting with an American art expert and her beautiful young assistant, Sue-Hannah van Evan, to assess the worth of the works inside. Sébastien does not want them to know about Nardi, so naturally Hannah and Nardi meet and are immediately fascinated with each other. Bliss is a superb romance, written in beautiful prose, suffused with real love of art history and fashion, and bought alive by memorable, vivid characters.

There is one moment in Bliss when Hannah and Nardi are in a meadow in Normandy and they see a monarch butterfly. “The fuck they did,” I said, because monarchs are a North American species. They don’t live in Europe. I thought it was a rare miss from the usually impeccable Cuevas. More fool me: monarchs are occasionally seen in western Europe, having flown across the Atlantic assisted by unusual weather. I didn’t find any clues as to whether this happened in 1903, but I have learned my lesson about doubting Judy Cuevas’s research.

Because Bliss is the story of Nardi and Hannah falling in love, obviously Nardi’s arranged marriage with Marie du Gard blows up. Sébastien is upset by what he sees as his addict brother failing him again—and because without the marriage, he doesn’t get his beloved Château d’Aubrignon back. He becomes the antagonist of the novel: he tries to keep Nardi and Hannah apart. So when I realized that Sébastien was the hero of Dance, I knew he would have an interesting journey to becoming worthy of falling in love—with who else but Marie du Gard. Romance novels are so efficient!

One thing marred these otherwise magnificent books for me. Marie is that unfortunately common archetype of 80s and 90s romance: a fat woman who loses weight so she can be a main character and get a happily ever after. I think Judy Cuevas is attempting something more complex and subtle than what goes on in most examples, but I don’t think she entirely succeeds. I’m not sure it’s possible to write any version of “she loses weight and finds love” without reinforcing some pretty vicious prejudices—are fat people not worthy of love?—and I’m glad that the genre now allows fat women as main characters. (There aren’t nearly as many fat men as main characters—or even slender men without defined musculature. Genre romance answering the question “are men people?” with the cruel shrug of “yeah, if they have abs.”)

Other than this disappointing treatment of weight, Marie is a marvelous heroine: brilliant, creative, independent, ambitious, a little surly. We meet her in Bliss as the daughter of a wealthy man, raised to be a society wife—and a threat to the heroine, Hannah, since Marie is Nardi’s fiancée. But instead of being a mean joke of a character, the sad fate narrowly avoided by the hero, Marie does something heroic: she cries off the wedding. It has nothing to do with saving Hannah and Nardi; she’s saving herself.

When we meet her again in Dance, we make the most wonderful discovery: Marie has shucked off her family’s expectations and their wealth to run away to the United States, where she has become a filmmaker. It’s 1906, so this is wild stuff! Cinema might be a fad. Marie comes back to France with her cameras in tow, dressing in rationally (scandalously) short skirts, smoking unladylike cigarettes, and consorting with unsavory artistic types. She rules. I wanna be her best friend.

By the way, the unsavory artistic type she’s consorting with is a painter named John Russell-Smith, and the book has this to say about him:

At sixty-nine, he was in all likelihood emotionally not very different from himself at thirteen, cultivating immaturity, knowing like the enfant terrible he was that his outrageous behavior could only add to his primacy, winning him undeserved compromise and attention. Despite this, Marie had liked him immediately. Russell-Smith was an original: unvarnished, unregenerate. His sadly banal behavior endeared him to her. It seemed to say, "Judge my art on its own; I myself am as unworthy of (and as uninterested in) homage as a self-centered child." Here was the quintessential artistic paradox, the divine delivered out of the heart of a flawed human being—an intelligent man supremely sensitive to beauty, form, refinement, who had to understand completely, and rather tragically, that the substance of his life fell so far short of these ideals as to be pure pathos. (52)

What a paragraph. Other writers have spilled whole books’ worth of ink about unworthy people making worthy art—how can this be, how can we live with it—and Judy Cuevas was like, give me half a sentence, I’ll get it done: “the divine delivered out of the heart of a flawed human being.” That’s all of us, really. Some of us are just falling a lot farther short of the ideals.

Part of Marie’s closeness with Russell-Smith is that he, as a “real” artist, believes in her as an artist. The rest of the world treats her short, comic silent films as frivolous and ephemeral, mere entertainment, certainly not to be classed with something as grand and important as oil painting. And, of course, these silly little throw-away treats are made by a woman, and they concern the misadventures of a female character falling in love, and they make the audience laugh and feel joy and perhaps even lust, so they couldn’t possibly be art.

You know, like a mass market paperback romance novel that sold for $5.99 in 1996.

One of the most delicious things about any Judy Cuevas/Judith Ivory romance novel is that it will be stuffed absolutely chock full of ideas. Art is a favored topic, as the passage above shows. In her author's note for Black Silk, she mentions setting that novel in 1858 so her characters could discuss Marx and Darwin, photography and aniline dye. Characters in Dance talk about cinema and Picasso and modernism. But they also talk about psychology and Freud and sexuality—because it’s 1906 and this is what interesting, well-read people would have been discussing at dinner after a long day of filmmaking. The particular early 20th-century setting of Bliss and Dance is unusual in genre romance—as is France instead of England—and it feels like such a deliberate, thoughtful, well-researched choice. Like the monarch butterfly in the meadow in Normandy that absolutely isn’t an accident, everything about this book is passionately on purpose.

I don’t mean to suggest that other romance novelists aren’t making purposeful choices about their art. I love this genre! I wouldn’t do that! But let’s put it this way: I’ve never seen anybody but Judy Cuevas use “deliquesce” in a sex scene. Her choices stand out.

At last we arrive at the sex scene. This isn’t even the best one in the book, by the way. But it had the word “deliquesce” and it made me kick my feet in excitement because it’s so rich and risky.

First, the setup. Marie and Sébastien have been orbiting each other for weeks, living in a rented house on the grounds of the Château d’Aubrignon. She’s there as a guest of Russell-Smith, making her film, and Sébastien is there because he went to visit the ruin of his family’s former château and then broke his leg and couldn’t leave. Forced proximity! Sébastien and Marie feel a powerful attraction to each other. He wants to pursue her, and even though he’s sure she likes him, she keeps evading him.

Unlike unconventional Marie, Sébastien is welcome in polite society. He’s male, he’s rich, he’s powerful, he’s educated, he has perfect manners and does everything right. He’s a very orderly, controlled person. He speaks perfect French and perfect, Oxford-educated English. He’s fit, he’s stylish, he has a neat little mustache and sometimes wears a monocle.

Sébastien attends the outdoor wrap party for the film’s cast and crew. He sees Marie slip into the woods. He follows her, discovers her on her knees in the leaf litter, and startles her when he asks what she’s doing. As it turns out, her cigarettes have slipped out of the pack and she is looking for them. Sébastien, partially recovered from his broken leg, lowers himself to the ground to help her search.

Then Sébastien muttered under his breath, “Your cigarettes belong on the ground where they are, with the rest of the dead leaves.” (240-241)

So we have this woodsy, natural setting, and both main characters are down in the dirt and the leaves, away from civilization and other people, and Sébastien is explicitly connecting Marie’s favorite secret vice, smoking, with “the dead leaves.” Things are decomposing around them. Order is becoming chaos. Rules are being broken. Uh-oh.

And then they see the mushrooms, chanterelles. This part I’m just including because it’s so pretty:

Within an arm's reach from where they knelt grew a stand of pale apricot-yellow mushrooms, the finest flavored, the most beautiful, like small flowers with their trumpet caps and delicate gills running down their stalks like knife-pleats. (241)

Mushrooms can be really phallic, but these aren’t. “Chanterelle” comes from Latin “cantharus,” which is a cup. So they’re “little cups” because of their shape. The “gills” in the text above are also called “folds,” so this is a flower-like, cup-shaped, delicious mushroom that releases a heady aroma from its folds, in case you wanted this to be more sexual.

Sébastien and Marie discuss how these treasures, rare and expensive to purchase in Paris (money, order, civilization, rules), simply grow for free in the woods (nature, chaos, freedom).

Marie makes a joke:

"So what happens to a mushroom in the forest if no one eats it?" The equivalent of: If a tree falls in the forest when there is no one around to hear it...

"It deliquesces." He had to use the English word, there being to his knowledge no equivalent in French, but the English word was nice. He liked it.

"It what?"

"It absorbs moisture from the air until it liquifies and melts away." (241)

There’s our word! Things becoming liquid. Melting away. That’s the sort of thing that happens in the privacy of the woods, you know.

Marie compliments Sébastien’s vocabulary (so educated!) and then wants to smoke. She asks him to light her cigarette, which he objects to, and he takes the cigarette from her mouth. He leans in close, tells her they smell bad, and then we get this magnificent passage:

He said, "They taste bad, too," then leaned forward and kissed her.

She tasted delicious; she didn't resist but rather let him have the whole of her warm mouth. She'd eaten the apple she'd carried earlier. He knew this particular variety by taste, by name all at once, the way, upon seeing a childhood friend, unmet for years, one suddenly pulls out a name along with a whole piece of forgotten history. Marie tasted of the honey-flavored Doux mouen—warm, soft, wet-mouthed, dewy, her lips faintly sticky with flavor, the heady taste of raw fruit and the best cider. As he played with her mouth, her tongue, gently kissing her, names rattled through his brain like poetry. Noël des champs, Calville, the sweet Bedan, the tart Binet rouge. His father tortured apple trees to grow against the house in Paris, espaliered, tied against a frame to grow flat against the wall, trained into a single plane of growth. This was different. The taste of windfall from his uncle's orchard here in Aubrignon. He and his brother had lived with his uncle off and on.

Kissing Marie's appley mouth was somehow like coming home, his real home, the fine old estate known as the Château d'Aubrignon. He took her shoulders and pulled her forward, bringing her off balance. She let out a sound of surprise when he turned her onto her back. And in the next moment she was lying half under him. He brought his full weight on top of her. (242-3)

First and foremost, are you fucking kidding me, how good is this kiss? This newsletter is less a close reading and more just me shoving paragraphs of this book under your nose and saying “Look!”

Second, Judy Cuevas, with the benefit of living in the future, knew that it was all the rage in early twentieth-century France to taste something that reminded you with sudden, vivid clarity of your childhood in Normandy. Our hero Sébastien, fictional and stuck in 1906, doesn’t know about Marcel Proust and the famous madeleine of Du côté de chez Swann (1913). But he’s got the spirit.

Third, this passage also offers a new perspective on wild, natural things made orderly: “His father tortured apple trees to grow against the house in Paris, espaliered, tied against a frame to grow flat against the wall, trained into a single plane of growth.” Tortured! Sébastien’s father is not a huge presence in the book, but brief mentions like this allow us to see how Sébastien himself became so espaliered—tied up, flattened, trained. His father’s Parisian apple trees, not gifted with a name like their poetic Norman cousins, don’t produce a fruit worth mentioning. Their purpose is not to grow flavorful apples, but to show off the gardener’s elaborate artifice. Certainly they don’t do anything so undignified as leaving one’s lips “sticky with flavor.” Raw and wet are right out.

And these sweet, tart apples Sébastien is reminiscing about aren’t harvested; it’s nothing so orderly as agriculture. They’re “windfall.” The trees shed them, by a simple, natural, wild process, and they drop to the ground.

In the countryside, hidden in the woods, Sébastien can shed his citified neatness and get back to his roots. It’s hugely important that this scene takes place on the forest floor. “Ground” and “earthy” show up a number of times in the text. Sébastien is a very collected, composed man, and the dirt is where things decompose. Other good things happen there too:

It was an earthy pleasure to press her to the ground, a boundless satisfaction that he breathed in, inhaling it along with the musty smell of damp leaves and moss and mushrooms from a forest floor. (243)

Here’s the next appearance of “earthy,” reclaiming pleasure even more triumphantly:

What he wanted of Marie suddenly did not feel beastly or dirty so much as earthy, messy, disinterested in neatness and fuss. (244)

Sometimes it’s good when things are messy!

I just wanna say again that the chutzpah it takes to wind this particular metaphor through a sex scene—to make decomposition sexy!—is singular. Judy Cuevas has the chops.

It’s so freeing to be outside in nature, to stop worrying about rules and neatness, to fall to the ground like a ripe, honey-flavored Doux mouen or a Binet rouge, to slip your hands under all those layers of leaves and touch the soft, wet, warm earth, where things turn liquid and decompose.

The words wet, soaking, steaming wet entered his conscious mind, as he rubbed himself against her. He touched, through wool and silk and underlinen, the delicate part of her that breathed out moist life like breath. (244)

“Underlinen” is such a marvelous word choice there. This is a turning point in the scene. As Sébastien touches, through many layers, Marie’s sex, the decomposition metaphor changes. It points toward what the earth does next: cradle and sustain life.

You can’t have apples without earth, or chanterelles without the forest floor. Those pleasures require a little mess, a little disorder, and so does sex. First you have to discompose yourself. Decompose yourself. Deliquesce:

He dug his fingers into the dry leaves, feeling the surprising heat just below their surface where leaves and ground met in ongoing process, last season's treefall melting in hot organic fusion, dissolving into humus. A deliquescence. He closed his eyes. He was going to die like the mushrooms, the chanterelles that filled his nostrils, melting, melting, liquifying... (244)

Hot organic fusion! Certainly the hottest organic fusion I’ve read. Prior to reading this scene, I’m not sure I would’ve believed it was possible, but you know, sometimes people see monarch butterflies on the other side of the Atlantic. It’s rare, but it’s real.

Whew. I'll be back in your inbox on February 1 and I promise next time I'll talk about books that are easily available to read.

Word Suitcase is a free newsletter about words and books. If you enjoyed this one, subscribe by email or RSS for the next one. If you know somebody who'd like reading these, please pass it along!

Websites do cost money, so there is a paid subscription option and a tip jar for one-time donations. If you feel moved to support me, I’m very grateful. But please don’t feel obligated. I love having you as a reader either way.